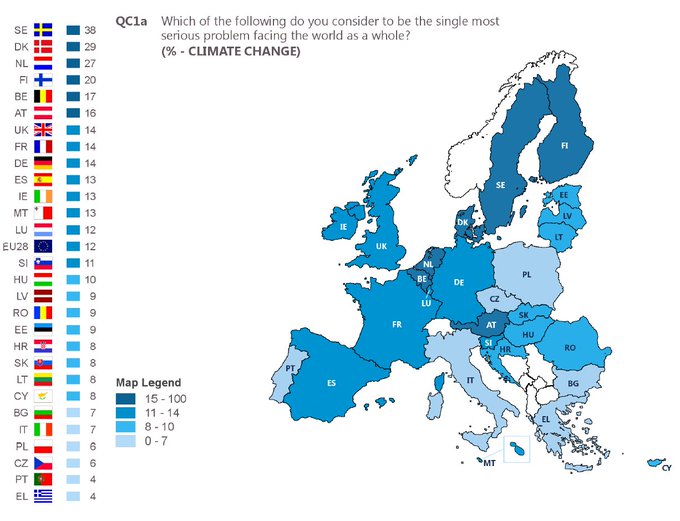

#EU: Significant differences in considering #ClimateChange as ‘single most serious problem’; new special @EurobarometerEUon climate change

Climatologist traces history of the meaningless 2-degree temperature target

Do you want to know the origins of the 2-degree temperature target that underpins much of climate policy discussions and action?

- As is often the case, it is an arbitrary round number that was politically convenient. So it became a sort of scientific truth. However, it has little scientific basis but is a hard political reality.

- Jaeger and Jaeger (2011) explain that it came from “a marginal remark in an early paper about climate policy”

- That “marginal paper” was a 1975 working paper by economist William Nordhaus (here in PDF and a second version is from 1977, with the figure shown below). At p. 23, “If there were global temperatures of more than 2 or 3°C. above the current average temperature, this would take the climate outside of the range of observations which have been made over the last several hundred thousand years.”

- Nordhaus’ claim was sourced to climatologist Hubert Lamb (1972) who in turn calculated long-term variations in temperature based on record kept in Central England.

- So: The 2-degree temperature target that sits at the center of current climate policy discussions originated in a local, long-term record of temperature variation in England, which was adopted by an economist in a “what if?” exercise.

- The 2-degree target is today far more politically “real” than its grounding in science or policy. That won’t change, but it is nonetheless a fascinating look at the arbitrariness of policy and how it is that issues are framed shapes what options are deemed relevant and appropriate.

- As an example, check out this paper just out today in Nature — it argues that we can emit more than we thought and still hit a 1.5-degree temperature target. People will argue about the results, many because of its perceived political implications. But this argument is only tenuously related to actual energy policies, instead, it is related to how we should think about arguments that might be used to motivate people to think about energy policies and thus demand action and so on. Tenuous, like I said.

Glen Peters explains why carbon capture and sequestration is a necessary part of any climate policy focused on deep decarbonization. It is neither a popular nor widely discussed issue outside of a few specialists.

Finally, for now, new polling indicates that climate change is not a high public concern in many parts of Europe:

Read more at The Climate Fix

Trackback from your site.